The Impact of the Pandemic to Street Life, Urban Culture and Beyond.

Maurice Harteveld, co-host and moderator of the roundtable discussion with speakers from the Netherlands, from Greece, from France, and from the United States.

Category Archives: culture of the city

Designs for Boston and Amsterdam

Propositions under Continuously Changing Urban Conditions

Massive urbanisation puts pressure on public space and demands new programmes along with alternative gathering places such as public interior spaces and a variety of forms of collective spaces. Moreover, in the rapidly changing city, infrastructure and mobility remain of vital importance. A co-evolving diversity of programme cannot be planned, but interventions in the city need constantly to be grounded on sharp design approaches to respond adequately to the necessities of the time: While being environmentally sustainable, given the available resources.

In general, infrastructure, mobility, and public life manifest themselves in various forms as carriers of such urban development. Design experiments, as put forward in our new book, show how to work with continuously changing urban conditions, with mobility transforming cities whilst with public spaces taking various forms, with programmes which hybridise, and with new technologies to keep up with the urban dynamics. Given these themes, designs should carry awareness of the inclusiveness and accessibility of various systems and places, facilities, and technologies. Spatially this means questioning how to keep the city open and connected, attractive, and liveable?

Continue reading

The Impact of the Pandemic to Street Life, Urban Culture and Beyond

We have seen a growing number of people have been hospitalised per day, and people passed away. Both followed the bell curve. Every country faced critical moments when hospitalised totals stressed the capacity of medical care. The uncertainty among the populations grew in that period. Particularly, the impact of the pandemic to street life became visible in those days. Cities locked down, people stayed at home, and shifts in urban culture became visible. Can we place those changes in a longer perspective? Looking back to what happened before, and forecasting what most likely happens beyond 2020: A Year without Public Space under the COVID-19 Pandemic?

Image created by Catherine Cordasco.

Submitted for United Nations Global Call Out To Creatives – help stop the spread of COVID-19.

Join the webinar!

When: Thursday, August 6, 2.00 – 3.30pm CET

> Registration

This webinar is part of the initiative ‘2020: A Year without Public Space under the COVID-19 Pandemic‘.

Continue reading

Mapping Maritime Mindsets: Mental Maps

Imagine: You are asked to draw a port city from memory. What would you put on paper? Do you think of harbours? Water, docks, cargo, moving loads, and ships? If your drawing shows these elements, don’t be surprised. Sixty-five graduate students also took on the challenge. In answering: “draw the port city of Rotterdam by mind”, the drawings of the participants (fig.1) displayed exactly the above features. Of course, this makes sense. A port just happens to be a place on the water in which ships shelter and dock to (un)load cargo and/or passengers. A harbour is a sheltered place too, and in its nautical meaning, it is a near-synonym for sheltered water, in which ships may dock, especially again for (un)loading. So, all the above linguistic lemmas are there and all these are connected to imaginable objects.

Keep reading on Port City Futures | Leiden•Delft•Erasmus

Port-Cities: Diverse and Inclusive

9 June 2020

Article by Carola Hein, Paul van de Laar, Maurice Jansen, Sabine Luning, Amanda Brandellero, Lucija Azman, Sarah Hinman, Ingrid Mulder, Maurice Harteveld (Leiden-Delft-Erasmus PortCityFutures)

Published on: Leiden Delft Erasmus universities network Magazine, June 2020, and on the website of LDE PortCityFutures

Rotterdam, photo by Iris van den Broek

Port cities are a particular type of territory and are often long-standing examples of resilience, bringing opportunities, wealth, and innovation to their nations and their citizens. They have developed at the crossroads of international trade and commerce and the intersection of sea and land. Flows of people through trade and migration have played a key role in their spatial, social and cultural development. Their strong local identities share legacies of diversity and cosmopolitanism, but also of colonialism and segregation. The Qingjing Mosque in Quanzhou, Fujian speaks of the exchange between Arabia and China along the maritime silk road. Hanseatic cities stand as an example of far-flung networks with districts for foreign traders—think of the German merchants who established Bryggen, the German dock, in Bergen, now a UNESCO world heritage site.

Port cities are places that accommodate change —and often thrive as a result. As logistical patterns, economic organization, spatial structures and technological devices have evolved, port cities have consistently provided spaces and institutions to host changing social, cultural and demographic needs and have built their local identities around them. Chinatowns, for example, are emblematic of many port cities worldwide. For many centuries, traders and merchants depended on the interaction between local traders and short- and long-term migrants of all classes. To maintain and facilitate shipping, trade or organizing defenses, traders, workers, and citizens have come together and developed long-term strategies and inclusive governance systems. Built around trade, these shared practices have not always benefitted everyone. Colonial port cities hosted the buying and selling of enslaved people as well as minerals, animals and opium. Many workers lived in squalid conditions in walking distance to the port. The degree of tolerance and inclusion depended on the extent of ethnic diversity overall, the degree of spatial and social segregation in the city, and the economic structure of the urban economy.

Waterfronts have been and in some (smaller) cities still are contact zones of people from diverse backgrounds: public spaces bring together dockworkers, displaced people, casual labourers, and trans-migrants waiting to board ships for overseas travel. However, waterfronts have been looked upon as places of otherness in need of social reform even at the turn of the twentieth century. Since the 1960s, container districts and offshore ports further increased the separation between ports and cities. Following containerization, waterfront regeneration has become a worldwide tool to overcome the range of social, cultural and public health issues associated with the nineteenth century waterfront. Urban renewal and gentrification have been central to many of these programs that took off beginning in the 1980s in most European port cities. Rebranding has been an essential part of bringing new capital and new people into neighbourhoods next to former dock areas, which normally would not have been of interest to private investors. In select cases—such as HafenCity Hamburg—planners and politicians have consciously opted for spatial and social inclusion.

Rotterdam as a port city reflects the long-term history of migration traditionally related to shipping and trade in all aspects, but since the 1970s the working port is no longer a decisive pull factor. Other international, national and local factors have changed the city’s population characteristics. The past decades have seen increasing diversity in ethnic groups and religions but also increased variation in socio-economic statuses among inhabitants with a migration background. Rotterdam hosts so many ‘minority’ migrants that it is now considered a superdiverse city where 52%, and in some districts, almost 70% of the population have a migrant background.

Rotterdam’s hyperdiversity—a term meant to acknowledge the multiple causes of diversity—has challenged existing local integration policies. The city government’s development strategy focusses on a balanced composition of the population and regeneration programs in combination with new residential, sustainable urban planning and branding strategies aim to assure integration. Like other cities with major waterfront revitalization activities, Rotterdam is witnessing a gap between cosmopolitan aspirations boosted by international capital and symbolic waterfront architecture and the existing reality of a hyperdiverse population inhabiting the urban fabric. Redevelopment projects of former waterfront port areas, such as Lloyd Quarter, RDM and M4H stand as examples. Yet, like other cities with major waterfront revitalization activities, the question arises: to what extent is Rotterdam widening the gap between diverse neighbourhoods and gentrified port-city redevelopment projects? There is a potential risk of economic segregation as authorities, educational and cultural institutions aspire to build the post-industrial economy on the port industrial foundations of the past, neglecting those areas where a linkage to the maritime mindset of Rotterdam as a port city is hardly felt let, alone visible.

Rotterdam needs to find ways to come to terms with political, economic, social, and cultural dimensions of its port city. That is one of the major challenges for Rotterdam in becoming an inclusive city. What is needed to connect Rotterdam’s migration narrative (and that of other port cities) to further the inclusive city ambition, using its present hyperdiversity, and acknowledging the value of diversity for creativity, innovation and making the next port city? Exploring the key values of an inclusive post-industrial, hyperdiverse port city drives the research agenda of our multidisciplinary LDE PortCityFutures program.

The Leiden-Delft-Erasmus PortCityFutures program employs multi-disciplinary methods and longitudinal perspectives to understand and design political, economic, social, and cultural dimensions of spatial use in port city regions. It explores how the flows of goods and people generated by port activities intersect with the dynamics of the natural environment, hydraulic engineering, spatial planning, urban design, architecture, and heritage. It examines the spatial impact of competing interests among port-related and urban spatial development needs and timelines. It explores creative solutions and design measures to problems and considers their implications for the future use of limited space that will allow port, city, and region to thrive.

Architecture in Urban Change

Designers are questioning what architecture of relevance could face ongoing change over a longer period in today’s most dynamic urban areas. Of course, answers are always specific and the search on how to respond to constantly changing urban conditions may be the only issue that is shared in all cases. Yet, still, there must be more commonalities in the wide range of answers. The set of design propositions as presented at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Versailles (ENSA-V) underlines this, while designs display a few recognisable approaches. Projects put the emphasis on the importance of intervening at strategic locations, of programming adaptive and responsive, hence flexible, and of imagining and creating expressions that will enhance public interaction and experience over a longer period. As a guest of the school, I have the opportunity to review these thoughts and discuss emerging approaches with prof Nicolas Pham.

l’Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Versailles

Champ disciplinaire de Théories et Pratiques de la Conception Architecturale Urbaine (TPCAU)

5 Avenue de Sceaux, Versailles

20 December 2019, 9:30-17:30h

Public Space in the Entrepreneurial City

New public spaces have emerged in the entrepreneurial city. Their existence relates to entrepreneurial action of public governments, of the people, inhabitants of the city, and of entrepreneurial alliances of civic actors. The entrepreneurial way of governmental action led particularly to new spatial conditions and typologies as governments delegated the responsibilities for the production and management of public space to private actors. This extended the debate to the city’s public space in its ubiquitous shopping malls and private residential estates. Secondly, the opportunities which the city offers for the entrepreneurial contributions of general citizens, migrants, and refugees, relate to its public spaces too. Characterised by the proximity of mixed land-uses and flexible building typologies, as well as a well-connected street network and high density, the new urban typologies, effecting public space in their socio-economic nature, are found in many places, using the same models concerning citizens initiatives and popular action. Lastly, new emerging alliances of actors form the relationship of the ‘entrepreneurial city’ and public spaces. These alliances of civil society groups comprise old and new NGO’s, academics and activists, and start-ups of social enterprises launch own initiatives to co-designs alternative community spaces, more affordable and communicative workspaces, and build capacities. Such trends can be seen in cities worldwide too and start to create new forms of public spaces, which facilitate social interaction while creating more micro-economic opportunities.

Read full editorial online:

Maurice Harteveld and Hendrik Tieben (eds) (2019) ‘Public Space in the Entrepreneurial City’, In: The Journal of Public Space (Special Issue), 2019, Volume 4, Number 2, pp. 1-8

Continue reading

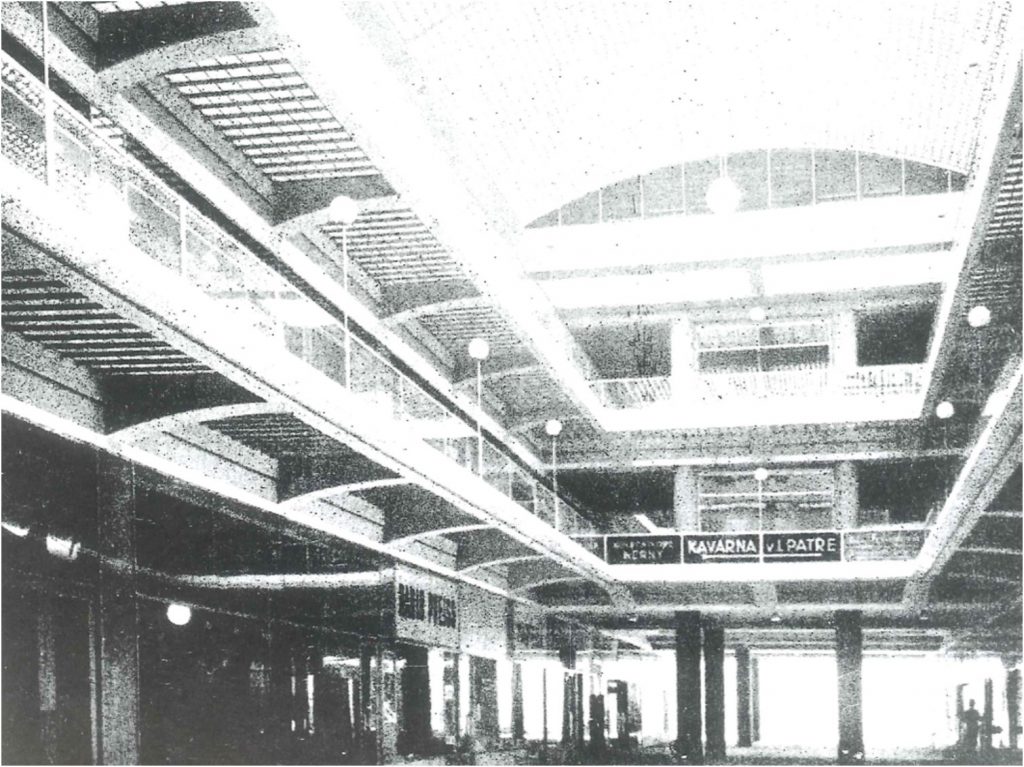

Pasáži Renesance

Prague has more arcades than Paris. Still, they are less known. This is unfortunate, because these arcades underlining the identity of Prague and the Czech Republic. This is underpinned particularly during the 1990s arcade renaissance. New arcades have been designed, like Pasáž Jiřího Grossmanna (1995 –1996), Rathova Pasáž (1996), and the redesign Hrzanska Pasáž of 1702-1704 (1996). These projects have upgraded existing arcade systems, introduced new styles, but foremost new hopes… It echoed an update on the Czech Awareness.

Throughout history we have seen this happen in the design of arcades in Prague. This particular study brings us back to the rise of Bohemian identity and unfolds an epistle illuminating an alternative arcade project. As such, the study reframes relations between design of public space and society and provides a way to understand shifts in these.

Pasáže Černé Růže (1936), by Oldřicha Tyla

Pražské Pasáže

Arcade Projects in Prague

Public Buildings | Urban Architectural Design | Contextual Assignment

as projects for people, and projects within Society

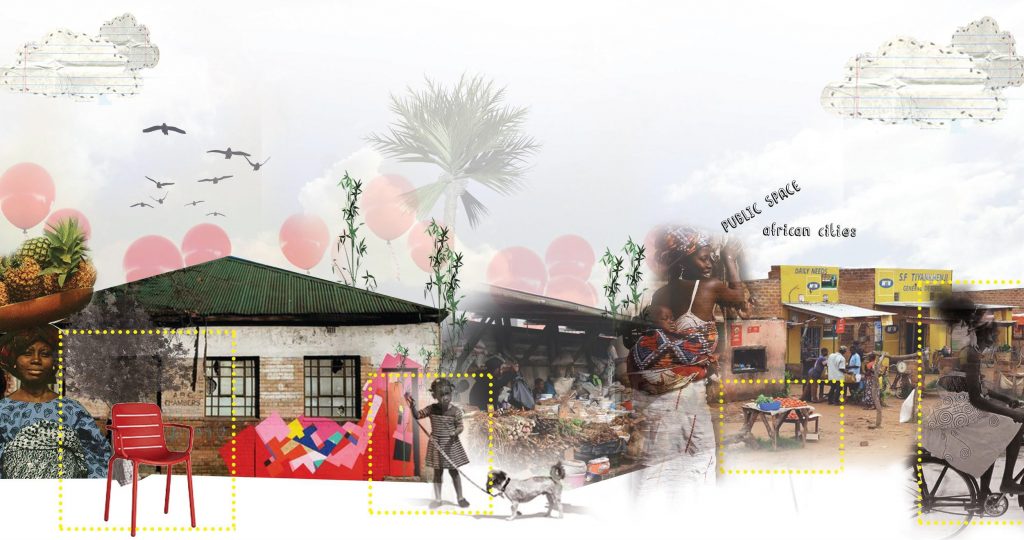

African Public Spaces?

What is public space in African? Does it exist as we may presume? At the current, we are analysing and comparing urban life and presumed public spaces in selected segments of four African cities to map what we know about these cities. It is a first step in deepening cross-cultural understanding: An exiting start of a new exiting scientific journey along Dakar in Senegal, Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, Maputo in Mozambique, and Lusaka in Zambia.

Image by Vaggy Georgali

Continue reading

Places of Being and Eternal Paths

Magic Lanes in Hong Kong displays an inspiring community-design project that aims at turning a street into a place for stimulating vibrant urban life, which is rewoven with the present contemporary social fabric. By mapping current use and envisioning potential use of urban space by local residents, the project has set a base for real-life experiments. These experiments highlight the spatial assets people own by nature. In responding to the rapid urbanisation of this early-developed neighbourhood, the project it encourages their participation in the street. Located at Sheung Fung Lane (常豐里), the space used to be an empty concrete urban space characterised by outdoor stairs and blind facades of the neighbouring parking garages, and foremost no people actually staying there. With this project, people have entered a process of place re-making. It seems the essence of what is a ‘li’ (里), because next to its contemporary connotation of ‘lane’, this notion is used more accurate as ‘place’. Yet, also, it is ironically strong because it works with the street name. The notions of ‘sheung’ (常) and ‘fung’ (常) refer resp. to eternal/unchanging and to plenty. As if, magically, a flower pot is always full of living flowers. The project incorporates the ideas of its community members and it facilitates physical changes in this space. If people are present it will be a place again.

一刻 社區設計館,西營盤常豐里2號怡豐閣7號舖

First Community Design Museum;

Shop 7, Yi Fung Court, 2 Sheung Fung Lane, Sai Ying Pun

At the same day earlier, I have also noticed that many streets in Hong Kong are known as ‘toa’ (道). Tao, which has a much longer history, means ‘way’, ‘path’ or ‘route’, and thus is translated simply as ‘road’ today. Philosophically, again de-contextualised, this notion represents the intuitive knowing that life cannot be grasped full-heartedly as just a concept. It relates to the path human beings are on. This path is known nonetheless through the actual living experience of one’s everyday being. This may make the presence of people in space, part of the same endless path we are on, wherever we are.

古之善為士者,微妙玄通,深不可識。

The ancient scholar is virtuous, subtly mysterious, deeply unknown.

or, as we may say at the present:

Once upon a time, those who knew the Way, were a mysterious and subtle people, transient yet profound, tranquil yet utterly unfathomable.

Chapter 15 (第十五章), Dao De Jing (道德經), attributed to Lao Zi (老子)