Good public spaces enhance community cohesion and promote health, happiness, and wellbeing for all citizens.

It has been with this quote that UN Habitat launched the Global Public Space Programme in an aim to improve the quality of public spaces worldwide. Of course, without doubt, the programme stands for a crucial challenge to make our urbanised world better, but what to do? The ideas on this have been matured and agreements seem to saturate the scope at the recent Habitat III conference held last week in Quito. A list of final set criteria is emerging, but this cannot mean that we’re done… By no means this listing will work if stakeholders do not accept that people gather on a variety of places around the globe, in a variety of cultures, hence not just in those urban spaces which are created by Western idealists’ minds: publicly-owned outdoor space.

Habitat II conference

The launch of the programme aimed for a better understanding of public space, important in promoting sustainable urban development. According to the rapporteurs the topic has not been given “the attention it deserves in literature and, more importantly, in the global policy arena”. Thus the programme searches for a emerging ‘body of principles’ and ‘sound policies’ for improving access to good public space in the urbanised areas of the world. At that stage, the answer was simple: a toolkit, as a practical reference. Something which local and central governments can use to mirror own approaches. And, a showcase, which demonstrate “the value of the involvement of the citizenry and civil society in securing, developing and managing public space in the city”. It was 2011, and the aim seemed clear.

The topic of public space has become omnipresent in discussing human settlements, since. A clear exemplary is given by a subsequent World Urban Forum, held in Medellín, where it has permeated the majority of the debates: In the closing report of that conference, a lot of the reported remarks on global urbanisation concerns, explicitly are issuing public space or urban space in general. We can count eight percent of the remarks, being present in almost every session. Sure, a conference theme of Urban Equity in Development – Cities for Life can only guide such discussions towards the quality of urban spaces for people, but still it is remarkable. Suddenly public space has become a hot topic for all nations. With conferences like this one, UN Habitat has deliberated on a new urban agenda for the next twenty years. The ideas, which have been securely prepared in New York City and other places have been presented at the recent Habitat III conference. In the line of reasoning, implementing the urban agenda for public spaces presumes urban rules and regulations, urban planning and design, and municipal finance. So, with ‘the rule of law’, we can establish ‘the adequate provision of common goods’, while ‘local fiscal systems should redistribute parts of the urban value generated’. This is more than a toolkit or showcase.

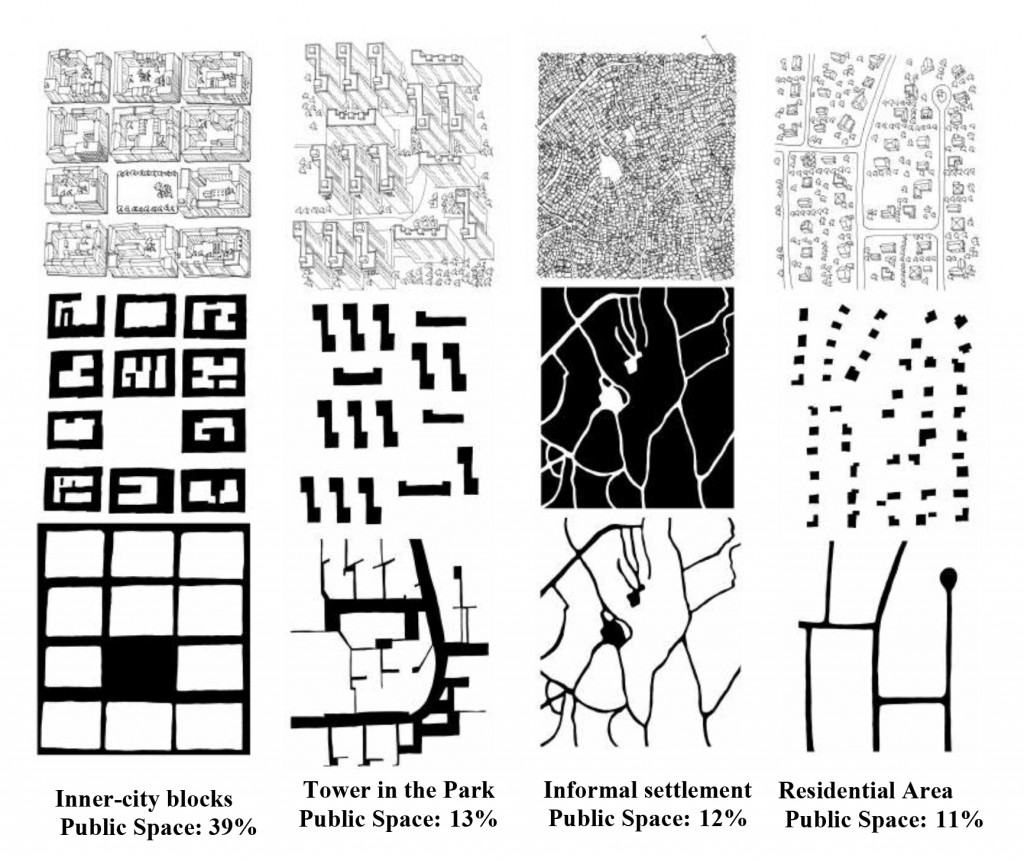

The aim has shifted! In the past years, UN Habitat has brought forward global desires and even general criteria: Good public spaces include the notion of equity, as in general accessibility of land, housing and decent work for all, irrespective of gender, age or physical (dis)ability, and as in general connectivity, reducing urban spatial segregation, making the city more inclusive, safe, prosperous and harmonious spaces for all, and increasing access to basic services, like safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport and proper sanitation. It includes the road network, horizontal and vertical networks, and for example aims clean mobility, lower density, walkability, visibility, local commerce, max. amount of parking lots. Though as promised showcasing a wide variety, the criteria for a good public space is acknowledged as much more. With among others a special UN interest in children and youth, meeting and learning in cities, and certain women groups, engaging, participating and empowering in cities, public spaces are seen as places for dialogue and democracy. They are aimed to be socially cohesive spaces, where people can meet and interact, being locally appropriated and populated with action. Places of liveability, for shelter, security, employment and entrepreneurship. Enhancing creativity, shared growth and creating multiplier effects, they challenge ways of thinking and acting, ways of using space, lifestyles, social and economic relations and consumption and production patterns. Populations are seen as co-producers. No matter if it concerns formal or informal spaces, the centrality of public spaces are expected to influence mixed use and social mix as a premise, yet multidimensional poverty, environmental degradation, and vulnerability to disasters and the impact of climate change may all be present and influence the quality of the space as is. By all means and media, in the public space, local and central governments have to safe-guarding public interest. Some even referring to a Taliesin of life and memory, preserving historical and cultural assets, it may be all very specific. A strong addition. Yet, the image we get in Quito tells a different story.

From Habitat III issue paper on public space, March 2015

In brief, the Quito Declaration on Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements for All echoes all of the above. It explicitly envisages cities and human settlements that are participatory, promote civic engagement, engender a sense of belonging and ownership among all their inhabitants. It prioritises safe, inclusive, accessible, green, and quality public spaces, friendly for whoever, whatever… ‘Leave no one behind’, by ensuring equal rights and opportunities, socio-economic and cultural diversity, and by integration in the urban space, enhancing liveability, health and well-being. It is indeed the attention which is needed. In Quito, special sessions on public space to celebrate this, have been supported by local side events to promote the value of public spaces: “Quito, a Public Space for People”. The credo is clear. Events support understanding where people are, while aiming for more, like the happenings entitled Track Your City, People-Friendly Route, Rediscovering The City, Making the Neighbourhood, Urban Design Lab, Pop-Ups on Placemaking, and even Pop-Up Public Space.

The Global Public Space Programme is now working in more than twenty countries, including Bangladesh, India, Kenya, South Africa, Peru, Haiti, Kosovo and Mexico. The programme focuses mainly on cities in developing countries with high percentages of their population living in informal settlements. Primary partners are cities and local governments who are often tasked with the creation and management of public spaces on the local level. This is very encouraging and for sure the programme will expand foci. Yet, as posed in the intro, by no means the listing ‘as is’ will work. It seems to presume that public space is always outdoors, owned and governed by local (and central) authorities, and known and used by all people.

Nairobi examples from left to right: (i) Mathare Valley Community Centre, (ii) Muthurwa Market Stalls, and (iii) recently opened Garden City Village; all planned, all part of urban life, all raising questions, all not in the generalist scope of Habitat III.

Who decided to define public space as such in these documents and sessions? Random people at random places around the world will acknowledge that that they come together as a community, a public, on different sites as well. New York City, home base of the UN, hosts for instance a wide variety of public spaces. Indoor atria, underground plazas, community gardens, malls, common areas, et cetera. Some of them are labelled by the City as official privately-owned public spaces (POPS), with all kinds of rules and regulations safeguarding local public interest and qualities. In this metropolis alone one may find a diversification of the phenomenon in every social and spatial direction. In addition, if one acknowledges that the fundamentals of the notion of ‘public’ lays in a Indo-European and/or Greco-Roman setting, and most parts of the world have (also) different roots, one will be introduced to new lessons. More so, the expectation is that the cities where the programme is landed will unfold a more mature approach to urban spaces for people. Public space is more than a street, a park, a square, or ‘Western’ idealist’ urban open space of such a kind. Taking cultural specificity serious, there will be someone at the meeting table who understands that ‘public’ space is more, has many faces, and not necessarily is defined in a way can be understood it in this global agreement. For example, if one stays close to the UN-Habitat Headquarters in Nairobi, one will discover that people flock together as groups in community centres too, essential for the cohesion between people and as such promoting the desired health, happiness, and wellbeing for its members. These spaces are part of the net together with the outdoor paths and places. Same may be true for the covered ‘timed markets’ in that city, which are said to be helping members of vulnerable groups, or recently opened premises, which integrate shopping, living and working for new middle class communities. Any kind of shared spaces can locally contribute to the scope; covered, indoors, not owned by the government, nor used by the larger public, perhaps not known by the people in the UN meeting rooms. From that point, it suddenly seems a silly starting point to have been expecting a toolkit for cities, which is applicable world-wide, or aiming for a generalist showcase of public spaces. No matter how strong human criteria and common aims for public space may be, relating them to specific places have to be the next phase. Many people make many urban spaces, and many urban spaces make many cities. That is what unites.

Selection of references;

United Nations Human Settlements Programme, UN-Habitat (2015, March) The Seventh Session of World Urban Forum, Urban Equity in Development – Cities for Life, Report

United Nations Task Team on Habitat III (2015, 31 May) Habitat III Issue Papers, 11 – Public Space, New York [during the UN Task Team writeshop held in New York from 26 to 29 May 2015]

United Nations Human Settlements Programme, UN-Habitat (June 2015, updated February 2016) Global Public Space Toolkit: From Global Principles to Local Policies and Practice, Nairobi

Habitat III (2016, 10 September) New Urban Agenda, Quito Declaration on Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements for All (adopted 20 October 2016)

See also:

UN: Public Spaces for All