In explorations of the notions of public space, public interiors are generally seen as undemocratic and more private spaces. This is based on the Roman distinction between publicus and privatus, but making public space, as a public case, refer primarily to res publica. – On the other hand, there is a related Roman public law that deals with the common interest of urban society, and could include cases of interior public space. Most sociological research in contemporary daily life reveals these spaces as public. For urbanism, this research can be seen as the social context, because the urbanist is primarily focused on the city: the civitas, and not the whole societas. More specifically, for urban designers who deal with public space, it traditionally means focusing on the outdoor space, and although this is almost always synonymous with the public domain or publicly owned space, I believe that public space can be more than this. For urbanism this means there is a need for new understanding and an extension of the design task..

It seems our notions of public and private have derived from a Roman distinction between ‘publicus’ and ‘privatus’, often underlining this by referring to the ‘res publica’. Yet, Roman public law was concerned with urban society by safeguarding a wider common interest. The ‘res publica’ was extended to the ‘res extra commercium’. At certain stages, Roman public law comprised three cases; (i) the ‘res divini iuris’, which involving the law of the gods or religion, (ii) the ‘res communes omnium’, involving the entire society, and (iii) the ‘res publicae’, involving what is owned by the government. As any redefinition of ‘public’ on this ancient base is very difficult today, still illustrated by this triad, we can question: what is most vital for the urban society at the present? Or more precise: What is, or should be, public or common in the contemporary city? Putting the prime focus on the city: ‘civitas’, and not entire ‘societas’? For contemporary urban designers, dealing with the public space, this presumes centering outdoor space, thus the publicly-owned. Yet, has this been true? If perhaps, is it still true? Society changes, so is the city and its pubic realm, thus public space.

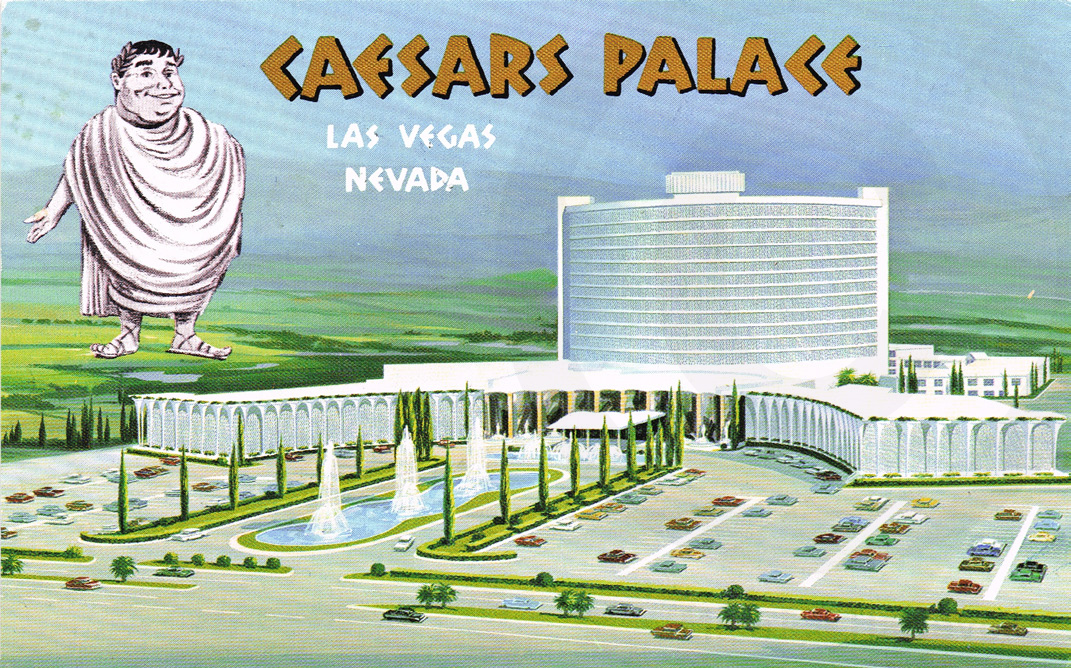

Caesars Palace, Las Vegas, 1968

Las Vegas gives us extraordinary examples. Here, buildings form urban structure, perhaps like always, but urban life in its local origin takes place inside. Without redefining ‘public’, we can start from the observation that indoor places are the domain of this society and from scratch an integral part of this city. Focusing on The Strip, we find 514 square miles of interior, most of which is publicly accessible. From Sahara (opened in 1952) to Mandalay Bay and Luxor (designed 1993-1999), we find all kind of public facilities. While some people watch Elton John playing the red piano at The Colosseum at Caesar’s Palace (corner-stoned in 1966), others visit the DKNY store and Siegfried and Roy’s white tigers between gambling at The Mirage (1989). Amazing hotels, incredible light shows, unforgettable performers in a place that seems unreal. Once it depended on the car for transport, now it is configured for collective forms of movement. Nowadays, the public buildings of The Strip are connected with moving sidewalks, monorails, walkways, and skywalks. The whole is covered, forming one huge network of interior public space. Of course along the interior network many restaurants with entertainment, but also small coffee places and main street bakeries. An ordinary H&M, simple book shops, and stores to do everyday groceries. Sure, also Dior. Day care and learning centres, pharmacies, health care service, chapels everywhere, churches nearby. Indoor fountains, plazas, benches, …is it different? Like shown in Nolli’s Las Vegas some decades ago, public buildings are part of urban use. Following Venturi, Scott Brown and Izenour, the designer’s aim is to derive an understanding of this new pattern. Although particular, with its hotels and casinos, it more. Downtown Las Vegas was losing retail and office tenants to the suburbs in the 1980s. Its gaming revenues had been lost to The Strip. With the design of Fremont Street Experience (1995-1996), the decline was not only reversed, but the design became the number one reason to visit. Today, especially in the cooler evening, historic downtown Fremont Street comes to life with a show of millions of lights and half a million watts of sound. It is part futuristic mall, part urban theatre. In the design an arched glass and steel roof has been introduced. Old main street is covered over, so even a drop of rain won’t discourage the public to come. From this angle, the quality of the public space has been improved and the space has attracted new investors and visitors. More so, the design of the enormous vault turned an outdoor lost space into an interior public space. Lofts, studios, small apartments of rental houses around the corner. Both the public interiors of The Strip and Freemont Street underline a demand for new understandings. To redefine the urban design task we should focus on the contemporary use of the urban network and the real public space in the contemporary city. A new approach to public space is needed. New maps should be drawn, redefining the public space, the urban design task, and today’s ‘res publica’?

This proposition is presented in brief as part of a research proceedings report, which includes a selection of research conducted at the Department of Urbanism of the Faculty of Architecture at Delft University of Technology.

see:

Harteveld, M.G.A.D. (2006) Viva Las Vegas, A Search for the Urban Design Task of Interior Public Space, In: Urban Transformations and Sustainability, Progress of Research Issues in Urbansim 2005, Amsterdam: IOS Press

read:

Google Books

Scribd